Cash flow is the real tabu, not developers’ salaries

Stepping back just a tad from an individual’s perspective, you’ll notice that your job and salary depend much more on the team’s collective assets than on personal negotiation prowess. And those assets hinge on the cash flow, which can easily be snagged by the first stone of indifference towards written proposals, specifications, and contracts. Here’s how we tackle this issue…

I don’t know if you’ve seen the billboard, but our industry has transitioned from a shitstorm to a clusterfuck mode of operation.

Zuckerberg lays off 11,000 people while simultaneously burning $36 billion just to draw flip-flops on avatars 🤷. Musk, in a similar layoff wave, argues with Twitter engineers over a $400 daily allowance for the cafeteria, while the FTX-stricken Genesis also struggles for survival, potentially dragging linked institutional crypto investors down with it.

I won’t dwell too much on the Sam Bankman-Fried subject, except for one thing – according to the bankruptcy trustee (and Nansen), SBF’s original sin was creatively patching holes in FTX Group’s cash reserves that initially emerged from the Terra / Luna / 3AC collapse.

By the way, the bankruptcy of Sam’s house of cards is twice as large as Enron’s case (handled by the same trustee), once again demonstrating that intoxicated crypto brothers are the greatest threat to the web.

But don’t immediately chant for the anti-crypto camp – based on the examples above, poor asset management appears to be the inherent vice of the entire tech sector. A decade of free money and consequently inflated valuations (from around 2010 to 2021) has made the industry lazy, so it not only neglected cash reserves, but they became the real taboo.

Of course, astronomical salaries and distasteful perks make for a more enticing tech-tabloid topic than cash flow itself, although the ironic reality is that your job and salary will depend more on team reserves than personal negotiation skills.

The times ahead are somewhat more complicated – viruses, earthquakes, wars, inflation, and now taxes on extra-profits (whatever that means) seriously reduce the financial maneuvering space for everyone involved. So today’s text won’t be focused on the described shady characters, but rather on ourselves, i.e., everyone managing personal or team budgets.

And unlike the personality cults chasing metaverses and unattainable robotaxis, the older tech players knew how to scrape the piggy bank…

The required thickness of cash reserves

Bill Gates mentioned in his (good!) Netflix documentary that he needs savings to cover at least 12 months of Microsoft’s expenses for a peaceful night’s sleep. Bezos was also obsessed with cash reserves for years – unlike its notoriously low displayed profit, Amazon consistently maintained a positive cash flow, and that has been the case since 2002.

However, the amount of money Jeff can torpedo into space isn’t as relevant to our region. In Croatian digital circles, the more interesting aspect is the service and project sector, which generates 60% of exports or 70% of total IT revenue. Such companies (e.g., agencies, project offices, and freelancers) will be the focus of this part.

Balancing on the edge

Let’s say you want to have a huge financial cushion and the most peaceful sleep in the world… you set money aside, save, and frugally “stash” every extra euro… With these actions, you’re leading your business into underinvestment because you’re not putting money into attracting new clients, product development, or learning new skills.

This approach has its limits in business rationale because your money as a resource isn’t being utilized enough (while it is for your competition). This situation is often seen in teams or freelancers who generate more than half of their income from a single client, i.e., they don’t systematically develop multiple sources of income (exposing them to other risks).

On the other hand, if you invest every penny in opening new positions, entering new markets, and launching all possible campaigns at the mention of the first buzzword… you’re navigating your organization into a cycle of overinvestment, and among other things, you expose yourself to the risk of not having the funds for upcoming salaries.

True, your money will be “better utilized” than the competition across the street, but at the same time, you risk shutting down the company if an unforeseen situation occurs (and SBF has demonstrated that “situations” come in pairs).

What the statistics say?

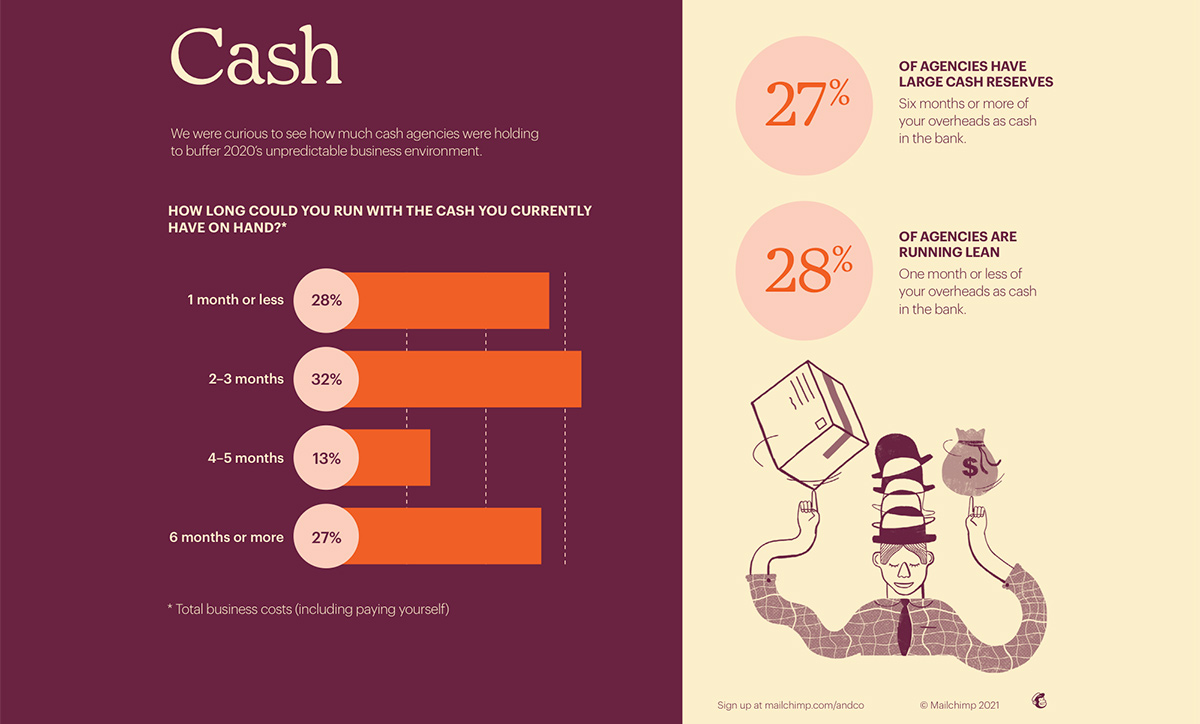

Accountants generally cannot give you a simple answer to the question “How much reserve is enough for me?”; however, Mailchimp comes to the rescue. More than 2,000 agencies and freelancers participated in a survey (PDF) that revealed only 27% of teams have enough money in their accounts to cover 6 months of operations (or more). At the same time, 28% of companies have reserves for up to one month. I assume this situation can be extrapolated to all types and sizes of service businesses.

Teams managing finances will want to have a thicker cushion (which is commendable), but the chart shows that companies with 6 or more months of cash reserves are in the minority. In other words: if you plan your business with, say, 7 or more months of cash reserves, you’re entering a cycle of declining competitiveness (underinvestment). Therefore, the idea is to save between 4 and 6 months of cash reserves.

In any case, the ideal thickness of the cushion will also depend on the desired “Fuck You” position that John Goodman masterfully portrayed on screen.

Filling reserves and pyramid-legal schemes

Alright, talking about the necessary cash reserves is an obvious concern (thank you, Captain Obvious), but realistically building up your current account is another ball game.

Problems with filling reserves arise because the dynamics of costs (expenses) and collections (revenues) are not the same. Costs are largely static and predictable, and in the digital industry, the majority goes towards gross salaries. In contrast, collections are variable and unpredictable. Consequently, profit (earnings) is variable and largely depends on the skill of smoothing out these fluctuations. This concept is called Cash Flow Velocity, and it would be presumptuous of me to claim that this article will illuminate the complete navigation through these calculations.

I don’t have room here to go through business planning, positioning, or investing, which will, one way or another, affect cash flow. However, there are proven “low hanging fruit/quick wins” tactics that could be useful:

- Split the payment into as many parts as possible. Let’s say you have a project with a total budget of 80,000 EUR. It is naive to tell the client that they will pay one installment of the full amount when “your job is done” because it opens up a multitude of future risks, the biggest of which is that one large installment will jeopardize the client’s cash flow. The entire card industry is built on this concept, i.e., to make it easier for people to part with their own money. IKEA doesn’t offer 36 interest-free installments for no reason – it’s to get as many people assembling Kallax as possible. The more installments, the easier the sale, and the more efficient the collection.

- Charge more at the beginning of the project. The amount of each installment can be the same (e.g., 10,000 EUR for 8 installments), but this does not accurately reflect digital projects and services. All projects require a larger allocation and more team energy at the beginning, as early decisions propagate later into design, programming, and maintenance. In other words, more people will be involved in the early stages of the project, and this moment should be generously budgeted (at least it should be). Therefore, it is wiser to have a pyramid-shaped payment plan – thicker early installments and thinner later ones. An additional benefit is that it ensures significant filling of reserves in case the project is terminated.

- If the client’s timing is crucial (Captain Obvious again), tie the installments to your service or project process – ideation, design, programming, testing… Each installment must be paid in advance at the beginning of each phase. The condition for moving to the next phase of work is the approved previous phase + payment for the beginning of the phase being entered. The “phase” of work can be a sprint for Scrum teams, a milestone for Waterfall teams, or a state for Kanban teams.

- If the client is slow, unsure about design, content, functions, or budgets the project from an external source (such as EU funds), which sometimes indicates their sluggishness… In that case, tie the installments to fixed monthly terms, not work phases. For example, the client will pay X thousand EUR every fifth of the month. Points 1 to 4 apply if you also work on a value-based agreement.

- The Time & Materials method of work (where every realized minute, hour, or day is charged, not the phase or value of work) is the simplest billing tactic. It is recommended to issue invoices to new clients more frequently than once a month, for example, weekly. Once you get in sync with the client and see how the whole process works, only then switch them to a monthly billing of hours. This will allow you to see their real attitude towards tasks and time calculation more quickly. The issue with the Time & Materials method is transparent hourly reporting, so you really need to make sure that the recorded working hours correspond to each work order. At Neuralab, we use a tight integration between Harvest and Trello systems for these processes.

- Produced UX, UI, and lines of code are copyrighted and your property by the act of creation. The transfer of intellectual property is done in writing, but only after the investor has paid all the listed installments and possible changes in functionality.

Communicate these 6 points to the investor as early as possible, all through the concept that many digital professionals have a stepmotherly attitude towards…

Estimate, contract and two smoking staples

Neglecting written proposals, specifications, and contracts is a common source of cash flow issues, and it’s actually a production loss, too. Well-prepared paperwork allows for smoother sailing through every activity.

On the other hand, poorly written and unclear documentation will undoubtedly lead to a worse project, product, or service – as veteran developers would say, garbage in, garbage out.

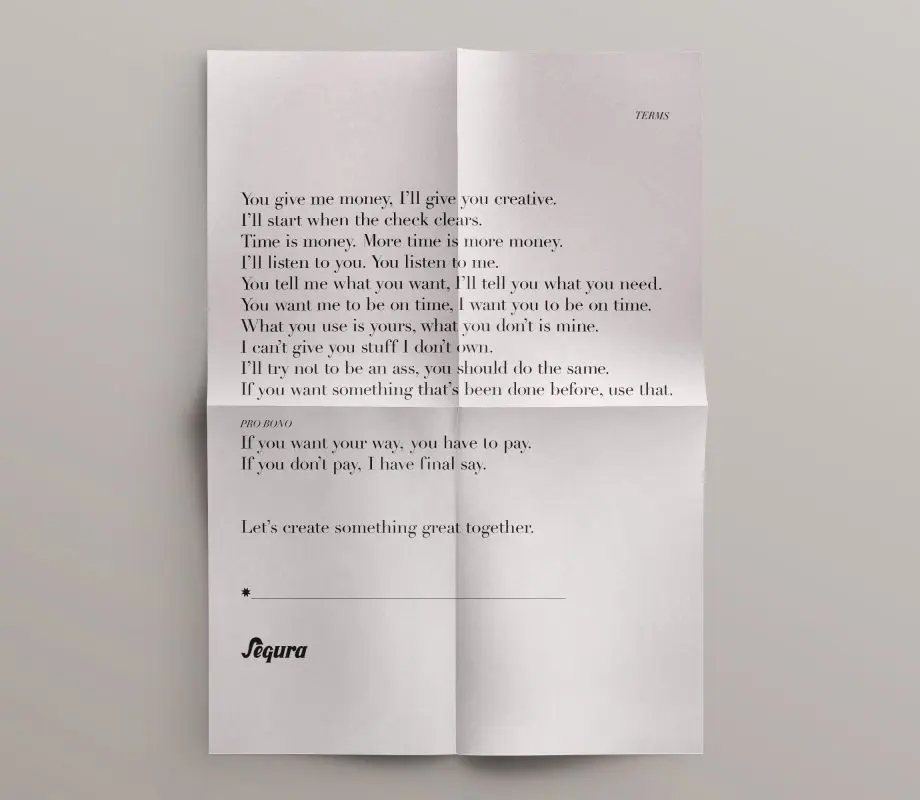

Mike Monteiro, the head of a design agency in New York, has an excellent talk on the subject of billing. However, the vast majority of the video is taken up by a “contract” and Mike’s lawyer. It’s telling that he, like John Goodman, yells “F*** You.” This time, from a legal standpoint …

Here’s where the crucial “timing” comes in – send the contract to your potential investor at the same moment you send the proposal. The proposal, or any Statement Of Work (SoW), needs to include all the business aspects that you should present to the client as soon as possible. Payment rates, what exactly is being done, how many working days your job will take, payment terms, communication terms – all are described through the contract.

The contract (like everything in business) is subject to negotiation, but neglecting to agree on the first six points should be out of the question for you.

For example, the other day a potential investor told us that “they don’t have a habit of making advance payments.” Now, most people might think this is the perfect opportunity to whip out a flamethrower, but in reality, such situations are an excellent opportunity for educating the client.

Advance payments, aside from being one of the better techniques for ensuring cash flow, also guarantee the seriousness and involvement of all parties. They help secure the availability of the team, equipment, and external suppliers.

Advance payments, installment plans, and retaining intellectual property rights are well-established elements in the knowledge sales industries. If a client absolutely refuses to agree to such terms, it’s primarily a sign of future toxicity and a moment to turn down the client – a topic we discussed in greater detail at Surove Strasti.

As you can see, this isn’t rocket science, and you can expect positive changes if you adopt even half of the text. Also, you can find Neuralab’s contract template ( HRV / ENG ) on GitHub, which contains all the points mentioned, so feel free to “fork” and modify it as needed.

However, there is a more critical truth than contracts, literal billing, and replenishing stocks

A plump cushion ensures financial freedom, which is actually the foundation of general freedom for a team or an individual – the freedom to innovate and create the way they believe products should be produced.

Innovation and creation on our terms, combined with proactive cash flow management, make for the best sleeping pill and a realistic framework for individual or team development.

It doesn’t matter in which direction our industry will grow or decline; removing the taboo from the topic of cash flow will ensure meaningful and constructive conversations about the benefits for our people – whether we’re talking about money, days off, or production-crucial ping pong balls.